If there is one thing the great men of history have in common it’s this: books. They read, a lot. Theodore Roosevelt carried a dozen books with him on his perilous exploration of the River of Doubt (including the Stoics). Lincoln read everything he could get his hands on (often recording passages he liked on spare boards because he didn’t have paper). Napoleon had a library of some 3,500 books with him at St. Helena, and before that had a traveling library he took on campaigns. The writer Ambrose Bierce, the Civil War veteran and an underrated contemporary of Mark Twain once remarked, “I owe more to my father’s books than to any other educational and directive influence.”

The point is: Successful people read. A lot. And what about us young, wildly ambitious people who want to follow in their footsteps? We have that hunger, that drive, and desire. The question is: What should we read? What will help us on the path laid out for us — and all that it entails?

Now a lot of the right recommendations are domain specific. If you want to be a writer, there are certain books you should read. If you want to be an economist, well, there are genres you need to deep dive into. If you want to be a soldier, there are others too. Still, there are many books that every person who aspires to leadership, mastery, influence, power, and success should read.

These are the books that prepare you for the top, and also warn against its dangers. Some are historical. Some are fiction. Some are epics and classics. These are the books that every man must have in his library. Good luck and good reading.

Biographies

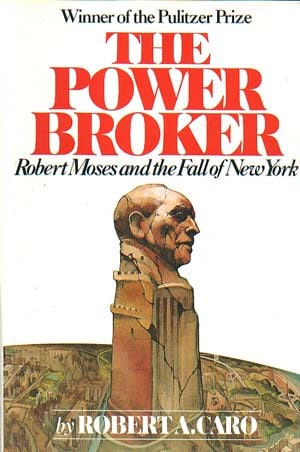

| The Power Broker by Robert A. Caro. It took me 15 days to read all 1,165 pages of this monstrosity that chronicles the rise of Robert Moses. I was 20 years old. It was one of the most magnificent books I’ve ever read. Moses built just about every other major modern construction project in New York City. The public couldn’t stop him, the mayor couldn’t stop him, the governor couldn’t stop him, and only once could the President of the United States stop him. But ultimately, you know where the cliché must take us. Robert Moses was an asshole. He may have had more brain, more drive, more strategy than other men, but he did not have more compassion. And ultimately power turned him into something monstrous. |

| Titan: The Life of John D. Rockefeller Sr. by Ron Chernow. I found Rockefeller to be strangely stoic, incredibly resilient, and, despite his reputation as a robber baron, humble and compassionate. Most people get worse as they get successful, many more get worse as they age. In fact, Rockefeller began tithing his money with his first job and gave more of it away as he became successful. He grew more open-minded the older he became, more generous, more pious, more dedicated to making a difference. And what made Rockefeller stand apart as a young man was his ability to remain cool-headed in adversity and grounded in success, always on an even keel, never letting excessive passion and emotion hold sway over him. |

| The Kid Stays in the Picture: A Notorious Life by Robert Evans. If you’re specifically looking to make your way in showbiz, this is the book you have to read. It’s the rags-to-riches, rise and fall and rise of Robert Evans, one of the most notorious figures in Hollywood. From pants salesman to running Paramount Pictures (and producing The Godfather), his story is the one that everyone who heads to L.A. hopes to have. It was one of the first books I read when I started working in the business. I think it shows you how far hustle and hype and heat contribute to success. And how they can also lead to your downfall and exile. |

| Empire State of Mind: How Jay-Z Went from Street Corner to Corner Office by Zack O’Malley Greenburg. This is a biography that also functions as a business book. It shows how as a young man in Brooklyn, Jay applied hustling techniques to the music business and eventually built his empire. A true hustler, he never did only one thing — from music to fashion to sports, Jay dominated each field, always operating on the same principles. As he puts it, “I’m not a businessman, I’m a business, man!” And related to that, I also recommend The 50th Law, which tells the stories of many such individuals and will stick with you just as long. |

| The Fish That Ate the Whale: The Life and Times of America’s Banana King by Rich Cohen. This book tells the incredible story of Sam Zemurray, the penniless Russian immigrant who, through pure hustle and drive, became the CEO of United Fruit, the biggest fruit company in the world. The greatness of Zemurray, as author Rich Cohen puts it, “lies in the fact that he never lost faith in his ability to salvage a situation.” For Zemurray, there was always a countermove, always a way through an obstacle, no matter how dire the situation. |

| The Autobiography of Malcolm X: As Told to Alex Haley by Malcolm X. I forget who said it but I heard someone say that Catcher in the Rye was to young white boys what The Autobiography of Malcolm X was to young black boys. Personally, I prefer that latter over the former. I would much rather read about and emulate a man who is born into adversity and pain, struggles with criminality, does prison time, teaches himself to read through the dictionary, finds religion, and then becomes an activist for Civil Rights before being gunned down by his former supporters when he tempers the hate and anger that had long defined parts of his message. Booker T. Washington’s memoir Up from Slavery and Frederick Douglass’s epic narrative are both incredibly moving and inspiring as well. |

| Personal Historyby Katharine Graham. If one thing is certain about your path to success, it is that it will be fraught with adversity. Fate will intervene in ways you would never expect. Which is why you absolutely must read Graham’s memoir. After the tragic suicide of her husband, who ran the The Washington Post and which they both owned, Katharine Graham, at age 46 and a mother of three, with no work experience to speak of, found herself overseeing the Post through its most tumultuous and difficult years (think Watergate and the Pentagon papers). Eventually, she became one of the best CEOs of the 20th century, period. She pulled through and endured with a strong sense of purpose, fortitude, and strength that we can all learn from. In similar regard, read Eleanor Roosevelt’s two-volume biography to see how she managed to turn what was at the time a meaningless position in the White House into a powerful platform for change and influence. |

How-to & Advice

| The 48 Laws of Power by Robert Greene. It is impossible to describe this book and do it justice. But if you plan on living life on your terms, climbing as high as you’d like to go, and avoid being controlled by others, then you need to read this book. Robert is an amazing researcher and storyteller — he has a profound ability to explain timeless truths through story and example. You can read the classics and not always understand the lessons. But if you read the The 48 Laws, I promise you will leave not just with actionable lessons but an indelible sense of what to do in many trying and confusing situations. As a young person, one of the most important laws to master is to “always say less than necessary.” Always ask yourself: “Am I saying this because I want to prove how smart I am or am I saying this because it needs to be said?” Don’t forget The Prince, The Art of War, and all the other required readings in strategy. And of course, it doesn’t matter how good you are at the game of power, without Mastery it’s worthless. |

| Steal Like An Artist by Austin Kleon. Part of ambition is modeling yourself after those you’d like to be like. Austin’s philosophy of ruthlessly stealing and remixing the greats might sound appalling at first but it is actually the essence of art. You learn by stealing, you become creative by stealing, you push yourself to be better by working with these materials. Austin is a fantastic artist, but most importantly he communicates the essence of writing and creating art better than anyone else I can think of. It is a manifesto for any young, creative person looking to make his mark. Pair up with Show Your Work which is also excellent. |

| Status Anxiety by Alain de Botton. Ah yes, the drive that we all have to be better, bigger, have more, be more. Ambition is a good thing, but it’s also a source of great anxiety and frustration. In this book, philosopher Alain de Botton studies the downsides of the desire to “be somebody” in this world. How do you manage ambition? How do you manage envy? How do you avoid the traps that so many other people fall into? This book is a good introduction into the philosophy and psychology of just that. |

| What I Learned Losing a Million Dollars by Jim Paul and Brendan Moynihan. There are lots of books on aspiring to something. Very little are from actual people who aspired, achieved, and lost it. With each and every successful move that he made, Jim Paul, who made it to Governor of the Chicago Mercantile Exchange, was convinced that he was special, different, and exempt from the rules. Once the markets turned against his trades, he lost it all — his fortune, job, and reputation. That’s what makes this book a critical part in understanding how letting arrogance and pride get to your head is the beginning of your unraveling. Learn from stories like this instead of by your own trial and error. Think about that next time you believe you have it all figured out. (Tim Ferriss recently produced the audiobook version of this, which I recommend.) |

Philosophy & Classical Wisdom

| Meditations by Marcus Aurelius. I would call this the greatest book ever written. It is the definitive text on self-discipline, personal ethics, humility, self-actualization, and strength. Bill Clinton reads it every year, and so have countless other leaders, statesmen, and soldiers. It is a book written by one of the most powerful men who ever lived on the lessons that power, responsibility, and philosophy teach us. This book will make you a better person and better able to manage the success you desire. |

| Cyropaedia by Xenophon (a more accessible translation can be found in Xenophon’s Cyrus The Great: The Arts of Leadership and War). Xenophon, like Plato, was a student of Socrates. For whatever reason, his work is not nearly as famous, even though it is far more applicable. This book is the best biography written of Cyrus the Great, one of history’s greatest leaders and conquerors who is considered the “father of human rights.” There are so many great lessons in here and I wish more people would read it. Machiavelli learned them, as this book inspired The Prince. |

| Lord Chesterfield’s Lettersby Lord Chesterfield. Just like Meditations, which was never intended for publication, this is a private correspondence between Lord Chesterfield and his son Philip. We should probably be happy that this guy was not our father — but we can be glad that his wisdom has been passed down. I have not marked as many pages in a book as I have in this one in quite some time. Of course, the classic in this genre of letters is Letters From A Self Made Merchant To His Son. Dating back to 1890, these are preserved letters from John “Old Gorgon” Graham, a self-made millionaire in Chicago, and his son who is coming of age and entering the family business. His letters are an incisive and edifying tutorial in entrepreneurship, responsibility, and leadership. Rilke’sLetters To A Young Poet is also moving and profound. Addressed to a 19-year-old former student of his who sought Rilke’s critique, these short letters are less concerned with poetry and more about what it means to live a meaningful and fulfilling life as an artist and as a person. |

| Plutarch’s Lives (I & II) by Plutarch. There are few books more influential and ubiquitous in Western culture than Plutarch’s histories. Aside from being the basis of much of Shakespeare, he was one of Montaigne’s favorite writers. His biographies and sketches of Pericles, Demosthenes, Themistocles, Cicero, Alexander the Great, Caesar, and Fabius are all excellent — and full of powerful anecdotes. These are moral biographies, intended to teach lessons about power, greed, honor, virtue, fate, duty, and all the important things they forget to mention in school. |

| The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects by Giorgio Vasari. Basically a friend and peer of Michelangelo, Da Vinci, Raphael, Titian, and all the other great minds of the Renaissance, Giorgio Vasari sat down in 1550 and wrote biographical sketches of the people he knew or had influenced him. Unless you have a degree in Art History it’s unlikely that anyone pushed this book at you and that’s a shame. These great men were not just artists, they were masters of the political and social worlds they lived in. There are so many great lessons about craft and psychology within this book. The best part? It was written by someone who actually knew what he was talking about, not some art snob or critic; he was an actual artist and architect of equal stature to the people he was documenting. |

| The Book of Five Ringsby Miyamoto Musashi. Widely held as a classic, this book is much more than a manifesto and manual on swordsmanship and martial arts. It’s about the mindset, the discipline, and the perception necessary to win in life or death situations. As a swordsman, Musashi fought mostly by himself, for himself. His wisdom, therefore, is mostly internal. He tells you how to out-think and out-move your enemies. He tells you how to fend for yourself and live by a code. And isn’t that precisely what so many of us need help with every day? |

Fiction

| This Boy’s Life by Tobias Wolff and Totto-Chan: The Little Girl at the Window by Tetsuko Kuroyanagi. If you wanted to read a book to become a successful, well-adjusted person, you probably could not do worse than Catcher in the Rye. Tobias Wolff’s memoir is a far better choice for the young man struggling with who he is and who he wants to be. I also suggest pairing it with the female counterpart: Totto-Chan. The latter is the memoir and biography of one of the most famous and successful women in Japan (akin to Oprah). It’s an inspiring little story of someone who didn’t fit in, who always saw the world differently (sound familiar?). But instead of making her hard, it made her empathetic and caring and kind — to say nothing of creative and unique. (The former is actually fiction but based on a true story. The latter is a true story but reads essentially like fiction). |

| The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz by Mordecai Richler. Duddy is the ultimate Jewish hustler, always working, always scheming, always looking for a deal, and looked down upon by everyone for his limitless ambition. Duddy never stops in his pursuit to acquire real estate in order to “be somebody” — never forgetting his grandfather’s maxim that “a man without land is nobody.” Except it doesn’t work out like he planned. From this book, you learn that the hustler — the striver — if he cannot prioritize and if he does not have principles, loses everything in the end. |

| What Makes Sammy Runby Budd Schulberg. A composite figure based on some of Hollywood’s first moguls, the book chronicles the rise and fall of Sammy Glick, the rags-to-riches boy from New York who makes his way through deception and betrayal. Essentially, Sammy is your Ari Gold without the slightest bit of human decency. He’s running from self-reflection, from meaning. It’s fear knocking on the door that he’s frantically trying to block with accomplishments. Sammy is an accomplished man, but not a great man — that takes ethics, purpose, and principles. All The King’s Men by Robert Penn Warren is another similar story — a sort of fictional version of The Power Broker — that tells of the effect that power and drive can have. |

| The Disenchanted by Budd Schulberg and The Crack Up & The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald. The Disenchanted and The Crack Up are both about the fall of F. Scott Fitzgerald, one from the first person perspective and the other from the fictional eyes of a friend watching his hero fall to pieces — just like the story of Gatsby itself. The Crack Up is a collection of essays, many of which are off-topic, but they had to be — a person cannot look so directly and honestly on their own broken soul without turning away at times. Fitzgerald’s Crack Up has always been illustrative to me and it’s something I’ve thought a lot about. I call it the Second Act Fallacy, and you pity and feel for a man with so much talent and wisdom who was helpless to apply it to himself. |

Liber medicina animi — a book is the soul’s medicine.

Of course, the books listed here are by no means all you need to be healthy or fulfilled. It’s just the beginning. But they do make a solid start to your library.

Enjoy and be careful out there. It’s a perilous road to the top.

________________________

Ryan Holiday is the bestselling author of The Obstacle Is The Way: The Timeless Art of Turning Trials Into Triumphsand two other books. He keeps a popular monthly book recommendation emailthat currently has more than 40,000 subscribers.